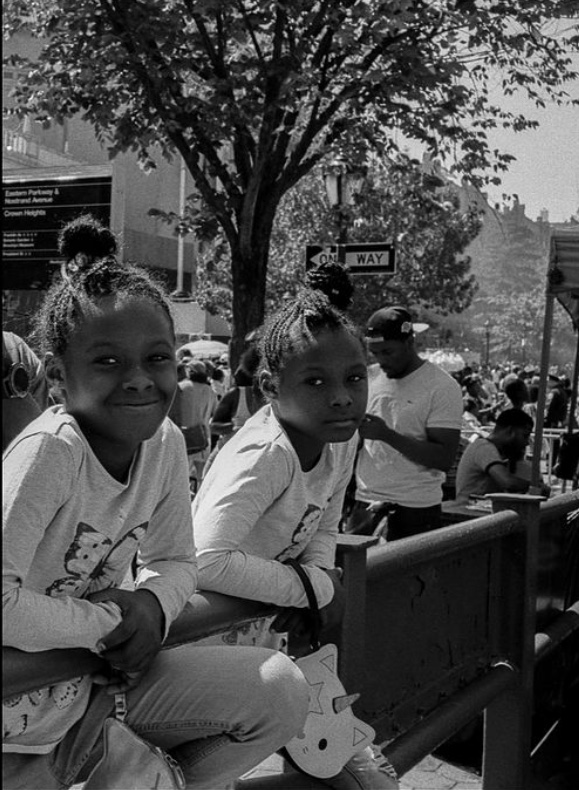

The Women that Raise Us. The name itself is powerful. When I hear the phrase I immediately think of motherhood, sisterhood, community, and as a dual thinker - the conflict that parallels these things. Syla Journal’s second installment covers movement through motherhood’s highs and lows gracefully and graciously, much like the journey of mothers of color. The virtual gallery is a collection of carefully curated visual and written works that pay homage, raise questions and provide answers to the theme. The interpretation of this art, as well as any other, is subjective and provocative. So as follows, here are my two cents of random thoughts pertaining to my favorite pieces from Syla Journal’s Installment II: The Women That Raise Us.

Excerpt from “Letters to the Women that Raised Me” by Zainab Floyd

As an admirer of all art forms, a stimulating visual is always appreciated and necessary. However, as a writer, I am always floored by the images we can paint with words. Zainab Floyd’s collection “Letters To the Woman Who Raised Me” captures both. A combination of raw portraits in intimate spaces, bold text, and sensory-driven language created an experience that drove me to think of my culture. Floyd’s collection raised the question of the differences and similarities between Afro-Caribbean women and Afro-Caribbean women of Hispanic descent. We share the love of plantains, rice, beans, spirituality, ancestry yet, I find the wedge between the two has been a controversial topic among us. I try my best every day to understand where the separation stems from so that I can help close the divide between two, otherwise, similar cultures. I am certain that this problem exists among many ethnicities, but being that my experience as a vessel on this earth is Caribbean, specifically afro-latin, I say this as a challenge to break a cycle of self-hatred in Afro-Caribbean communities of all descents. We owe it to black womanhood to address the ways that we can be anti-black, even in our own black skin. In her piece, Zainab asks her mother, “Mommy how do you carry so gracefully? How do you carry your pain so silently?” I would ask any Afro-Caribbean woman that same question, regardless of their descent. The reality of this shared plight in itself is the point and the exclamation.

Excerpt from “Be Gentle, Don’t Cry” by Dakotah Aiyanna

“Be Gentle, Don’t Cry” by Dakotah Aiyanna brought me to tears with one poignant line: “The woman who raised me has to be raised herself.” This poem chronicles a daughter realizing that she must learn to do a mothers’ work in order to keep a lineage of strength, despite trauma and mental health issues. At the end of the piece, it dawned on me that as we - the daughters - sift through our own childhoods in an attempt to break cycles and undo the mistakes that our mothers have made, we don’t often take time to forgive the fact that our mothers are daughters too; that a lot of us were being raised by girls who were not yet women. We see our mothers as mothers first and not as humans first, when in reality they were learning and earning their way, while simultaneously attempting to raise us. It takes a lot of time and healing to reach the kind of enlightenment that allows for forgiveness, but once I arrived here, I was able to look at my mother who was once a daughter, who lost her mother and thus her guidance at the age of eleven - then look at myself and say, “Ma, you are not perfect, but you did a damn good job.”

Excerpt from “How I Learned to Play the Crying Game” by Nia Mora

In a short but powerful 4 verse poem, Nia Mora captured the essence of mothers telling us how to work but not how to live, how to be tough, but not how to be soft. As a millennial, I often find myself in “Your generation” debates with older people, and while we have our flaws I firmly believe our strengths supersede them. Yes, we’ve been somewhat coddled by technology, but we’ve also made connecting with the world more accessible by it. Yes, some of us don’t “respect our elders” but we’ve learned to respect ourselves enough to not tolerate belittling or disrespect from anyone of any age. Lastly, we’ve decided collectively that we would be the ones to live out our wildest dreams. More leaders, less sheep. We will never be tied down by society’s obligations because we’ve obligated ourselves to lead fun, full lives. We are still purposeful, we just know how to work and play. With that being said, our elders have taught us, but they can also stand to learn from us. I know someone’s aunty is going to read this and question my audacity but quite frankly, I don’t care. So, to my generation: Never lose your fervor.

Excerpt from “Rules. Mommy, Daddy: Loving, Caring” by Sabrae Danielle Smith

Lately, the presence of alpha women in the places I frequent have been forthright. We are owners, bosses, rebels, scholars, artists assertively taking our place in male-dominated spaces. Through narrating her parents as characters in a short story, Sabrae Danielle Smith depicts an image of an outspoken woman and a quiet, seemingly submissive man. “Mommy used to tell Daddy, ‘Mind your business,’ when he insisted that she wear shoes outside. Mommy said, ‘You don’t have to do what men tell you to do, but be prepared for what could happen if you decide to say no.’” This line begs the question, are we putting ourselves at risk by being assertive? Indeed, we are. Every day as we make the decision to speak our minds, to defend our bodies, to simply demand respect - we risk our lives. But the freedom that comes from safeguarding our dignity, I’d say, is worth the risk.

As I wrapped up my experience with The Women that Raise Us, it occurred to me that I owe a lot to many women because mothering doesn’t end nor begin with bearing a child. I’ve been nurtured and raised upright by sisters, homegirls, tia’s, teachers and of course, mothers. For that, I thank all of the women who have ever contributed to my being. All of the women that raised me.

To experience the full installment visit SYLA Journal

- Nameless

P.S. S/o to Mama Nameless